Mountak monster remains found on Australian Beach? By Nepalikhabar24hour August 10, 2022

Where were you in 2008, and – more importantly – what was your favorite mysterious flesh? I know what mine is…

I’d love to revise the 2011 extinct rabbit-neck article, and I thought I’d republish something else from the archives (remember: almost all previous Tetrapod Zoology articles are published at ScienceBlogs and at Scientific American has now been marred by formatting issues or being paid (!!!)). And so, let’s take a look back at a classic TetZoo article… my 2008 article on the Montauk Monster. The text is slightly updated (with a new addendum at the end) but different as it was written at the time. I hope you will enjoy seeing it again…

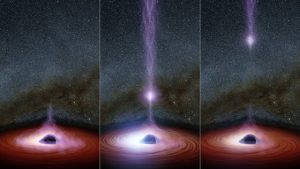

Caption: the original Montauk Monster photo, most familiar. Some claim that they can see the ‘beak’, others claim that there is a ‘strap’ on the animal’s right wrist. This original photo appears to have been taken by Jenna Hewitt. While this photo was the first to appear online, it appears to have been taken after Pampalone’s photo, shown below.

Unless you’ve been hiding under a rock, or spent all of your time at the Tet Zoo, you’ve almost certainly heard of the ‘Montauk monster’, a mysterious corpse that (apparently) drifted on the day July 13 [2008] at Montauk, Long Island, New York. A good photograph of the carcass, showing it in the right view and without any reference to proportions, appeared on July 30 [2008] and has been posted all over the internet. Given that I’ve only recently spent a week posting about sea monsters, it’s fitting that I mention this as well. I’m pretty sure I know what it is, and I’m glad to see many others reach the same conclusion, as evidenced by the many well-informed comments that popped up at Cryptomundo and elsewhere last week. . So, what is the Montauk monster?

..

..

Caption: the carcass as seen from its right side, now making it even clearer than before that the ‘beak’ is the consequence of the nose and associated facial tissues having rotted away. The existence of greyish fur on the body is also obvious. Photos by Christina Pampalone.

What has caused widespread confusion and speculation is that, while the lower jaw appears to have had a jagged row of pointy teeth, the upper jaw sports a hooked bony beak. This structure has led to the carcass being termed a “rodent-like creature with a dinosaur beak”, as an “eagle-dog’“ and to suggestions that it might be the carcass of a turtle that had lost its shell. Because these suggestions are all, to put it mildly, a tad unlikely, there have also been murmurings of a hoax or viral ad campaign. A ‘graphics expert’ at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service noted that, if it is a fake, it’s a very good Photoshop job, and the fact that the carcass became involved in a sort of marketing campaign for a soft drink hasn’t really helped in the credibility stakes (it is, however, pretty obvious that this was a case of opportunistic advertising). Rather more realistic (given the presence of fur and small, clawed hand digits) is the suggestion that it’s a dog.

The body is stocky and robust and the limbs are slender and gracile. The digits on the hands are slim, elongate and with small, relatively straight, pale-coloured claws. The slim tail is about equal in length to the head and neck combined. The face is short and it looks like the postorbital part of the skull is long and bulky. While no teeth at all are visible in the upper jaw, the lower jaw clearly contains a large pointed canine and four post-canines with tall, conical cusps. These teeth increase in size posteriorly.

Taphonomy in action. This is clearly a dead mammal, and its large canine and sharply cusped post-canine teeth show that it’s a carnivoran. The two details that make the carcass look odd – the lack of hair over most of the carcass and the supposed beak in the upper jaw – are clearly taphonomic artifacts. For years I kept watch on the dead things that washed up at a small stretch of tidal river bank in Southampton, and on several occasions I got to watch taphonomy in action as dead dogs, cats and foxes washed up and decomposed over the following weeks.

Caption: the decomposing remains of a domestic cat, partially buried in the sediment of the beach shown above. It was one of several carcases I found and studied during my long-time observation of events at the beach. Image: Darren Naish.

One of the first things that happens to bodies that roll around in the water is that their fur comes off, and they look grotesque, hair-less and bloated. The facial tissues then decompose, leaving a defleshed snout and eventually a totally defleshed skull. At the same time, the skin on the hands and feet is lost. Yet the body remains intact. Unfortunately I never took photos demonstrating this sequence of events (these observations were made while I was working on taphonomy for a book that never happened: for more on that particularly unfortunate episode go here).

The Montauk Monster therefore owes its bizarre appearance to partial decomposition. The tendency for the soft tissues of the snout to be lost early on in decomposition immediately indicates that the ‘beak’ is just a defleshed snout region: we’re actually seeing the naked premaxillary bones. And this is confirmed by new photos which show without doubt that this is the case (oh well, so much for the eagle-dog hypothesis).

Caption: a Raccoon skull. Compare the shape and tooth configuration with that of the Montauk Monster. Image: Pengo/Peter Halasz, CC BY-SA 2.5 (original here).

Is the carcass that of a dog? Dogs have an inflated frontal region that gives them a pronounced bony brow or forehead, and in contrast the Montauk Monster’s head seems smoothly convex. As many people have now noticed, there’s a much better match: Raccoon Procyon lotor. It was the digits of the hands that gave this away for me: the Montauk carcass has very strange, elongate, almost human-like fingers with short claws. Given that we’re clearly dealing with a North American carnivoran, raccoon is the obvious choice: raccoons are well known for having particularly dextrous fingers that lack the sort of interdigital webbing normally present in carnivorans (Lotze & Anderson 1979). As you can see from the composite image shown below, the match for a raccoon is perfect once we compare the dentition and proportions. The Montauk animal has lost its upper canines and incisors (you can even see the empty sockets), and if you’re surprised by the length of the Montauk animal’s limbs, note that – like a lot of mammals we ordinarily assume to be relatively short-legged – raccoons are actually surprisingly leggy (claims that the limb proportions of the Montauk carcass are unlike those of raccoons are not correct).

Caption: I am nothing to do with the creation of this excellent image. Its source is obviously marked on the image, but still I get asked for permission to re-use. Well done and thank you to the original creator.

Like all of these sorts of mysteries, this one was fun while it lasted, but the photos that really clinched it for a lot of people weren’t (so far as I can tell) released on the same day as the initial, tantalizing mystery photo (the one shown at the very top of this article). And I don’t mind this sort of thing too much: we get to see a lot of dumbass speculation, sure, but the immense interest that these stories generate show that people – even those not particularly interested in zoology or natural history – have a boundless appetite for mystery animals. If only there were some clever way of better utilizing this fascination.

Caption: it’s possible that the Montauk Monster event caused the biggest ever visitor spike at TetZoo… the daily high points here are in the tens of thousands, something I don’t think I’ve seen since.

Update for 2021: the 2008 article you’ve just read resulted in a fair bit of fall-out and follow-up. It partly became the main ‘go-to’ source on the raccoon-based identification of the specimen, the consequence being that Tetrapod Zoology – for a time – was receiving tens of thousands of hits each day, so many that my hit counter crashed repeatedly. This also meant that I was featured a few times on TV shows devoted to the case, typically being wheeled in as the sceptical expert debunker who disputed the populist narrative that the carcass “can’t be explained”. One of these shows even brought in another expert to test the argument that it could be shown to be a raccoon… but (I’m pleased to say) did have him back me up.

Caption: at left, the TX card for Alien Investigations (the creature depicted there is a deceased and modified marmoset, claimed by its main proponent to be an alien humanoid photographed alive after getting caught in a trap). At right, a shot from Wild Case Files showing me pretending to work in the palaeo lab at the University of Portsmouth. While doing the filming I discovered that we actually had a raccoon skeleton on the premises, and it’s posed at right.